The World's First Llama as a Service (LaaS)

In this article, I detail the development process and system design behind Llama as a Service (LaaS), a website and public API that delivers random llama images. It explores the challenges and solutions involved in building a scalable and efficient system.

This is a walkthrough of the development process and system design engineering for the Llama as a Service. LaaS is a website and public API that can serve random Llama images. It will respond with a single image URL, or even a list.

- Visit the LaaS website for a demo

- View the source code on GitHub

- View the walkthrough YouTube video

What I Learned

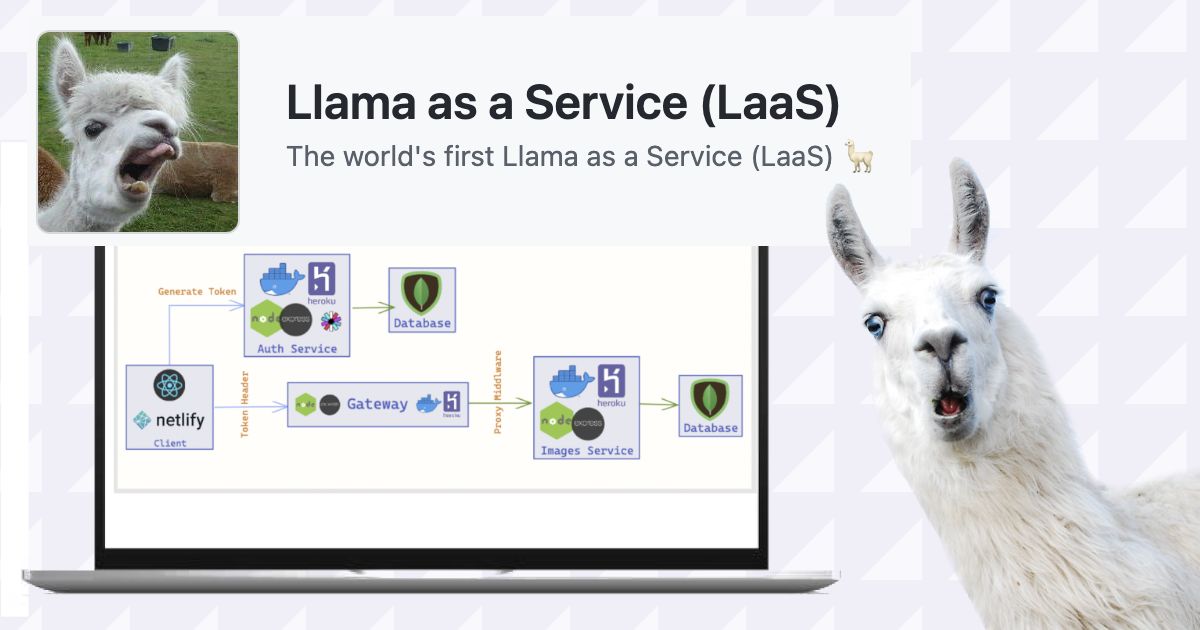

For this project, there is a frontend built with React hosted on Netlify, connected to the backend.

I built each API with Node.js, Express, and Docker. Services connected to a NoSQL MongoDB database.

Each service is in an independent repository to maintain separation of concerns. It would have been possible to build this in a monorepo, but it was good practice.

Each repository uses GitHub Actions to build, and test the code on every push. Express API was deployed to Heroku when the main branch was pushed.

With each app containerized with Docker, this allows it to be run on any other developer's machine also running Docker. Although I had automated deployments to Heroku without this, I decided to upload each service to a container registry.

Each repository also used a GitHub Actions workflow to automatically tag and version updates and releases. It would then build and publish the most up to date Docker image, and release it to the GitHub Container Registry.

For future use, this makes it crazy easy to deploy a Kubernetes cluster to the cloud, with a simple docker pull ghcr.io/OWNER/IMAGE_NAME command. However, that was beyond the

scope of this project because of zero budget.

To manage the environment variables, I was able to share Secrets to the GitHub Action workflows, which are encrypted, and can be shared across an entire organization (meaning multiple repos could access the variables). This allowed me to deploy my code securely to Heroku, without ever hard-coding the API keys.

Another tool I used was Artillery for load testing on my local machine.

Instead of npm, I tried using yarn for the package manager, and it was WAY faster in GitHub Actions even without caching enabled.

Although they did not make it into production, I experimented with the RabbitMQ message broker, Python (Django, Flask), Kubernetes + minikube, JWT, and NGINX. This was a hobby project, but I intended to learn about microservices along the way.

Demonstration

Here is a screen shot of the LaaS website.

If you would like to try out the API, simply made a GET request to the following endpoint:

https://llama-as-a-service-images.herokuapp.com/random

Creating an API

First, I started with a simple API built with Node.js and Express, containerized with Docker. I set up GitHub Actions for CI to build and test it on each push. This will later connect to the database, to respond with image URLs.

Although this API doesn’t NEED to scale to millions of users, it was a valuable exercise for building and scaling a system. I aimed for a minimum latency of 300ms with 200 RPS.

Image Database

With an API ready to connect to the database, it was time to choose between a NoSQL or SQL database.

The answer is obvious for this use case. Let’s walk through the data we have, and the use cases.

We are going to store one single table with image URLs. This could easily be done in either database, but there is one key factor. We need a way to randomly pull a list of images from the database.

A SQL database makes it simple to query a random row, however, this is not horizontally scalable, and with a large data set, we are replicating the ENTIRE database to each new node.

On the other hand, NoSQL databases are horizontally scalable; which leads me to Cassandra, but unfortunately it is very difficult to pull random selections from this type of NoSQL database.

Finally, I settled with MongoDB, which has a built-in $sample method to pull from the records.

Once I got the MongoDB database running locally with Docker, I created a quick script to seed the database.

Now it’s time to connect the API to the database.

Connecting API to the Database

Next, I used the mongoose Node.js API to connect to the local MongoDB.

I created two endpoints; one to upload an image URL, and another to retrieve a random list of images.

Endpoint Load Testing

To experiment with scaling the API, I wanted to do load testing. Keep in mind that this API does not have much logic, meaning caching, or optimizing the code's performance, will have a huge impact.

I found a tool for load testing called Artillery. Following this guide I installed Artillery and began research for the test configuration.

The API currently has the /random endpoint to return an image URL (a string), with very little computation. Let’s stress test this to see the current traffic limit.

The random list endpoint is what we need to optimize. For the starting algorithm though, I seeded 100 image records into the database, and then pulled the ENTIRE list from the database each request. The API would then choose 25 random elements to return. Let’s benchmark how this performs with load testing.

With the first run, API, the limit on the /random?count=25 endpoint was 225 RPS over 15 seconds, with 99% of the response times were under 300ms. We can improve this.

Optimizing the Endpoint

We have many records of image URLs in the database. Somehow, we need to efficiently transform these into a list, pulling random selections from the database.

Let’s optimize the query for pulling documents from the database. Using a special mongodb query, we can drastically reduce the computational load for a single request. Running

locally in postman, random?count=25 endpoint went from ~150ms for a single request, to <50ms.

This is the only code we need for this endpoint, compared to the previous 20 lines and O(n^2) space.

With the new query, the endpoint maintains 99% sub-300ms response time with a max of 440 RPS over 15 seconds.

Horizontally Scaling the API

With the containerized Node.js/Express API, I could run multiple containers, scaling to handle more traffic. Using a tool called minikube, we can easily spin up a local Kubernetes cluster to horizontally scale Docker containers. It was possible to keep one shared instance of the database, and many APIs were routed with an internal Kubernetes load balancer.

Horizontally scaling the API to two instances, the random endpoint maintains 99% sub-300ms response time with a max of 650 RPS over 15 seconds. Three API Instances => 99% sub-300ms response time with a max of 1000 RPS over 15 seconds. Five API Instances => 99% sub-300ms response time with a max of 1200 RPS over 15 seconds.

In practice, five instances were the limit of scaling the API horizontally. Even with more instances, the traffic was never sub 300ms response time. Note, this is dependent on the hardware of my local machine, and not accounting for cross-network latency in the real world.

With scaling, we can achieve higher throughput, allowing more traffic to flow, and resiliency, where a failed node can simply be replaced.

Since the image responses are intended to be random, we cannot cache the responses. It would be possible to scale the database with a slave/master system, but without a large data set, it is not worth the time to test. The bottleneck is most likely the API and connections to the database, versus MongoDB not handling read requests. It may be possible to improve the read times with a REDIS database, using in-memory caching, but that is overkill for this project.

Setting up Authentication

After playing around with load testing, I wanted to explore JSON Web Tokens and build an API to handle authentication.

This auth API will generate tokens, which will be sent back to the client as headers. The tokens headers are stored client-side (e.g. cookies, local storage), and sent to the backend each request.

If we expand the backend, we could include the authentication logic in each microservice.

Not practical. Instead, we can decouple the logic into its own service as shown below:

Creating a Gateway API

Instead of exposing the users directly to each microservice, we should route ALL traffic from the clients to the Gateway API. For this, I chose the same tech stack of Node.js/Express. Using a library, I was able to set up a proxy to the other services. In the future, this could be very useful to standardize requests to the backend, track usage, forward data to a logging microservice, talk to a message broker, and more.

Environment Variables and Configuration

Most of the system built, I needed to simplify the process for configuring the Docker containers locally, and how environment variables would be shared to each. Keep in mind, each service needed to access these in GitHub Actions as well, during deployment.

I used the docker-compose files to easily spin up the containers locally. I used default values for the environment variables for local development, and kept the config files

separated so it was easy to follow.

This step was just a process of carefully writing the Docker and docker-compose files, and setting up GitHub Actions Secrets. The code could not run without having all env variables, could be hard to debug locally or lead to ambiguity for other developers.

A Simple Frontend

I would talk about building the frontend, but it is just a single page React app I built quickly. It does use a CSS library called Bulma, which is similar to tailwind and worth checking out. I did spend a day implementing a login/signup page, but this was just for the learning experience, and not what I wanted in the final product.

GitHub Actions Testing and Deployment

With most of the code written, it was time to deploy the app. This was actually a bumpy road because I was not sure how to approach this. I was keeping each component in its own repository on my personal GitHub Account, which was getting hard to keep track of.

My solution was to create the Llama as a Service GitHub Organization, which also allowed me to store organization-wide secrets that any repository could access.

Using GitHub Actions, I created workflows to build and test code on every push, and deploy to main branch Heroku (and Netlify for the frontend).

I also created a workflow to tag and version every update, and release the Docker image to the GitHub Container Registry. These packages could be private to the organization, or public. I did not end up using these published containers, but it was really dope to see everything automated.

Deploying to Production

So after deploying the gateway API, frontend, and backend, I hoped all the services would be connected in production. For some reason the http-proxy-middleware was causing problems, and it was not worth redesigning the whole system. I was not ready to work with deploying a Kubernetes Cluster, so I did not use the GHCR Docker packages for deploying.

Instead, I just stripped away the extra services that I had been working on, and stuck with a simple system to deploy. For the final product, there is the frontend deployed on Netlify, which connects to the API on Heroku, with talks to the MongoDB Atlas database (in the cloud).

View the Source Code

If you wish to view all of the source code for this project, you can look through each repository here:

- GitHub Organization: github.com/llama-as-a-service

- All the GHCR Packages: github.com/orgs/llama-as-a-service/packages

- Frontend - github.com/llama-as-a-service/frontend

- Images API - github.com/llama-as-a-service/images-service

- Authentication API - github.com/llama-as-a-service/auth-service

- Gateway API - github.com/llama-as-a-service/gateway-service

If you want to have a repository with Node.js, Express, and Docker set up with GitHub Actions, check out the boilerplate repository here

Follow my journey and connect with me here:

- LinkedIn: /in/spencerlepine

- Email: spencer.sayhello@gmail.com

- Portfolio: spencerlepine.com

- GitHub: @spencerlepine

- Twitter: @spencerlepine